1900 King's and the Staffing of empire

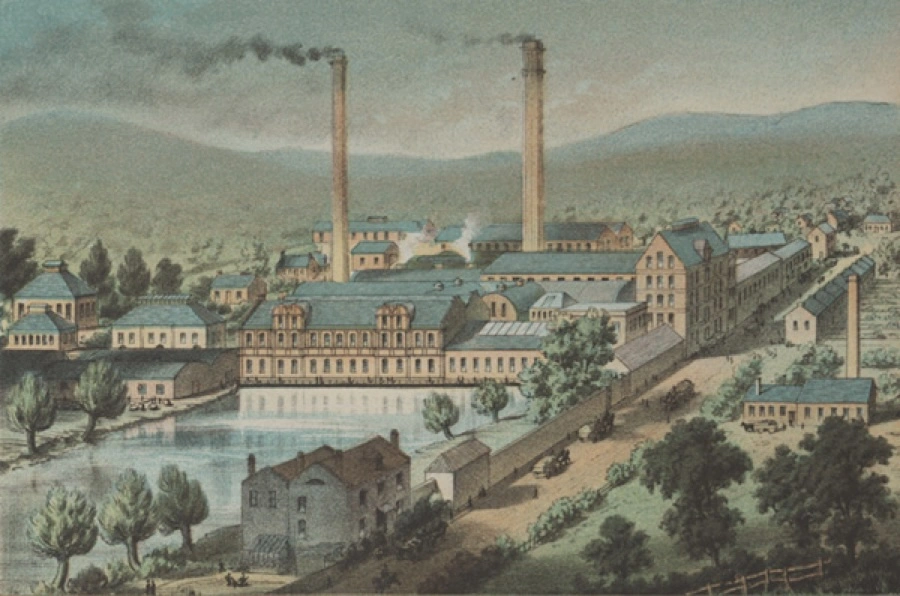

By the 1850s King’s had established a close relationship to the East India Company, and Britain’s government of India. This provided both employment for former students and opportunities to expand the university’s teaching. Engineering, Military Studies, Oriental Languages, and Law all had close connections to the East India Company. In terms of teaching, they were structured to provide training and generate new knowledge for those contemplating careers in India and the wider empire, while several of the fellowship transferred directly from working for the expanding imperial state to teaching in Higher Education (and vice versa). The East India Company made a donation to King’s upon its founding and continued support into the 1850s. King’s continued to supply officials and etchnical experts to various branches of the Indian Civil Service throughout the second half of the nineteenth century and a growing number to the Colonial Service during the twentieth century. Dozens of engineers were recruited from the King’s Department of Applied Science to the imperial Indian engineering service, for example. Involvement in the training and supply of imperial recruits shaped the college’s academic portfolio. As part of the University of London, the college continued to deliver pre-deployment training and used this commitment to appoint new chairs and lecturers in fields relevant to empire, including civil engineering, history and Asian languages.

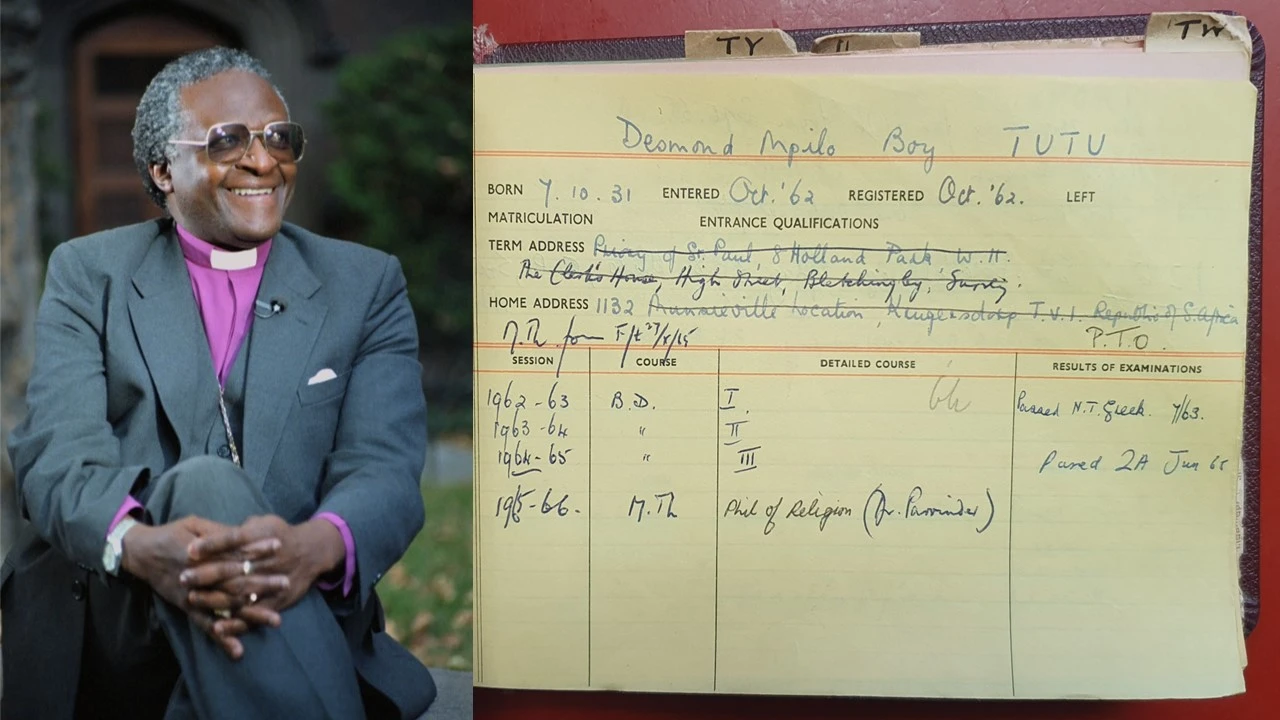

King’s future. King’s careers

King’s has had long connection to powerful institutions, in central London and elsewhere. It has, historically, helped sustain a political and administrative elite, but has also been a route for students from non-elite backgrounds into elite careers, in spheres from finance to the civil service. How should the university now guide and supports students on their career paths? How can it encourage graduates to exercise the roles they hold with a sense of responsibility? Should the university take responsibility for directing students towards certain careers?